After more than 35 years working with thermoelectric generators (TEGs), the most critical limitation I’ve encountered is heat flux management, not module efficiency. While thermoelectric modules are often rated for high power output, those ratings assume idealized boundary conditions that are rarely achievable in real-world systems.

Engineers always ask me what is the efficiency of the devices we sell, and I tell them it’s not about efficiency as design and material restrictions!

Like photovoltaic systems, TEGs do not scale linearly with size. Increasing module count or thermal input within a confined footprint leads to excessive thermal resistance and heat flux bottlenecks. With current aluminum and copper heat-spreading materials, it becomes increasingly difficult to move sufficient thermal energy into and out of the thermoelectric junctions to maintain an effective ΔT across the modules.

This conclusion is based on extensive empirical testing. Since 1996, I have designed, built, and tested approximately 80 complete TEG systems. And worked with another 300 to 500 clients, building their own systems. My earliest system used two solid aluminum plates (½″ thick × 5″ × 8″) with centered through-holes and liquid-based heating and cooling. Despite using six modules rated at 5 W each, the system produced only ~1 W total output under realistic operating conditions. The theoretical ΔT of 300°C/30°C was unattainable due to thermal coupling losses, interface resistance, the need to use hot water and heat spreading limitations.

Over the next 16 years, I iterated through roughly 30 internal additional designs. Some came close in demonstrated sufficient performance, and or cost efficiency to justify patent protection until 2012.

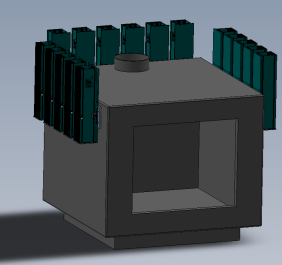

The first IPOWERTOWER™ prototype utilized two 40 mm thermoelectric modules in series, operating at approximately 290-310°C (Heat SINK) on the hot side with a 600C flame and 80°C on the cold side. Initial output was ~3-4 W. By modifying the thermal architecture—specifically by improving hot-side heat sink surface area and reducing overall thermal path length—the second-generation design achieved ~6 W with identical thermal inputs, even though the hot side was now 265-275°C. This showed how well my improvements reduced thermal bottlenecks!

Attempts to increase output by adding additional modules resulted in diminishing returns. Each added module increased thermal resistance and reduced average ΔT, yielding only ~1 W of incremental gain per module—insufficient to justify increased material and system costs.

The breakthrough came from recognizing that system-level thermal optimization matters more than module count. Passive cooling and thermosiphon-driven convection allowed stable operation, extended DT’s and therefore more overall consistent power output over extended times without parasitic power losses. When integrated with high-efficiency DC–DC conversion, designed specifically for the Nominal loads, therefore electrical conversions were in the high 95 to 98% using an MVPT algorithm, the system provided regulated 5 V USB output and 12 V battery charging.

Further output improvements—from 6 W to approximately 10 W—were achieved through proprietary thermal interface designs and heat flow management strategies detailed in my patent, which you have to look up. I just can’t hand over all my secrets!

Critically, larger monolithic systems consistently underperformed. Optimal performance is achieved by deploying multiple identical units in series or parallel, distributing thermal load over a larger effective surface area while maintaining manageable heat flux per module.

In thermoelectric power generation, distributed scaling outperforms centralized scaling. Bigger systems are not better—better thermal architecture is.

Marketing-Oriented / Customer-Focused Version

Why Bigger Thermoelectric Generators Don’t Work—and Why IPOWERTOWER™ Does!

Another way of saying it!

After 35 years of hands-on experience with thermoelectric generators, I’ve learned a simple truth: you can’t force heat to behave. Too much heat in too small a space kills efficiency, reliability, and performance.

Many thermoelectric systems fail because they try to do too much with a single large unit. Just like solar panels, thermoelectric’s work best when power is spread out—not concentrated. When heat can’t flow efficiently, power output collapses.

I’ve built and tested nearly 80 thermoelectric systems since my first prototype in 1996. Early designs used large aluminum blocks, liquid heating, and liquid cooling, yet still produced only a fraction of their rated power. That’s when I realized the problem wasn’t the modules—it was how heat was being managed.

It took 16 years of testing, refining, and rebuilding before I developed a design worth patenting. That design became the foundation of the IPOWERTOWER™.

The IPOWERTOWER is engineered around one core principle: efficient heat flow, not brute force. By using a compact vertical design, passive cooling, and thermosiphon-driven airflow, it extracts usable power without pumps, fans, or wasted energy.

Early versions produced 3 watts. With improved heat transfer and optimized geometry, output doubled to 6 watts—without increasing fuel or heat input. Further refinements, now protected by patent, pushed output even higher.

Most importantly, the IPOWERTOWER™ doesn’t rely on being oversized. If you need more power, you simply add another unit. Multiple IPOWERTOWERS™ can be connected in series or parallel, allowing you to scale power while keeping heat flux under control.

The result is a modular, portable, reliable power solution capable of:

- Charging phones via USB

- Charging 12V batteries

- Providing backup power where traditional electricity isn’t available

With thermoelectric’s, bigger isn’t better. Smarter design is. And that’s exactly what IPOWERTOWER™ delivers.

10 watts version

MODULAR SCALE TO 180 watts VERSION